In the last few workshops, we’ve looked at laying down the foundation for writing a story, from developing an engaging protagonist, forming an interesting premise, and coming up with a theme that will drive the plot, protagonist, and her arc forward.

Which leaves us with coming up with a plot for our protagonist.

Plotting is possibly one of the most time-consuming and intimidating parts of planning a book, but it’s absolutely crucial for even pantsers to have an idea of the direction they intend their story to go. While theme, premise, and even characters can come somewhat naturally for pantsers, plots often take concerted effort to think through, because without a connection between the events, they become nothing more than a series of episodic adventures.

One of the ways around this that can work for both plotters and pansters is by forming your plot around your protagonist’s arc. This works especially well if you have a protagonist-focused story (which we talked about here) but it can work for more complicated cast-focused stories, as well, creating a multilayered and often multi-perspective story.

To be clear, in this Workshop we are just going to be outlining a plot — getting the core ideas and concepts around each event down on paper (or, in this case, a white board) before we start writing. Each of these beats need a lot more fleshing out if you’re a plotter, but especially for pansters, following this method can give you a very loose framework of the flow and direction of your story without trapping you into a strict set of events that might lose your interest or feel too restrictive. Later on, I’ll do another Workshop on how to flesh these events out, but plotting is such a massive project that for now we’re just going to look at getting some very basic ideas down — and doing so in a way that directly serves your protagonist’s arc and your story’s theme.

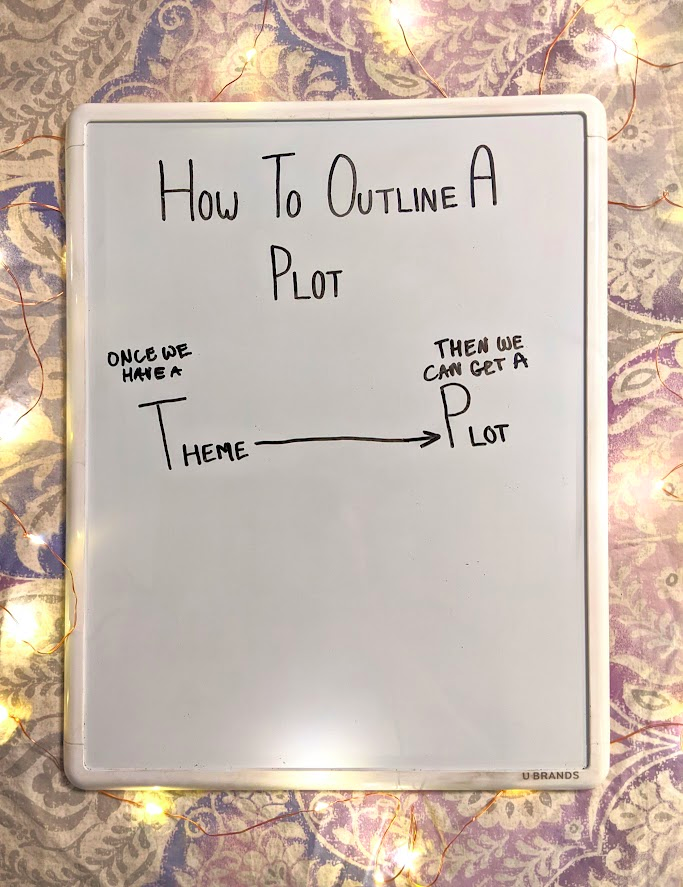

Plot and Theme

The first thing to understand when plotting is that your theme and plot work directly together. That’s why the last workshop focused on finding a theme — because without a theme, it is very difficult to have a cohesive plot. You can have an exciting series of events, but there’s no guarantee that they will end up pointing to the theme you realize works best for your story by the end. Some events or character moments might not even address the ideas in your theme, and since theme directly correlates to how relevant your events seem to your story, you can end up with some very irrelevant-seeming plot points — even if they are crucial for your plot or worldbuilding.

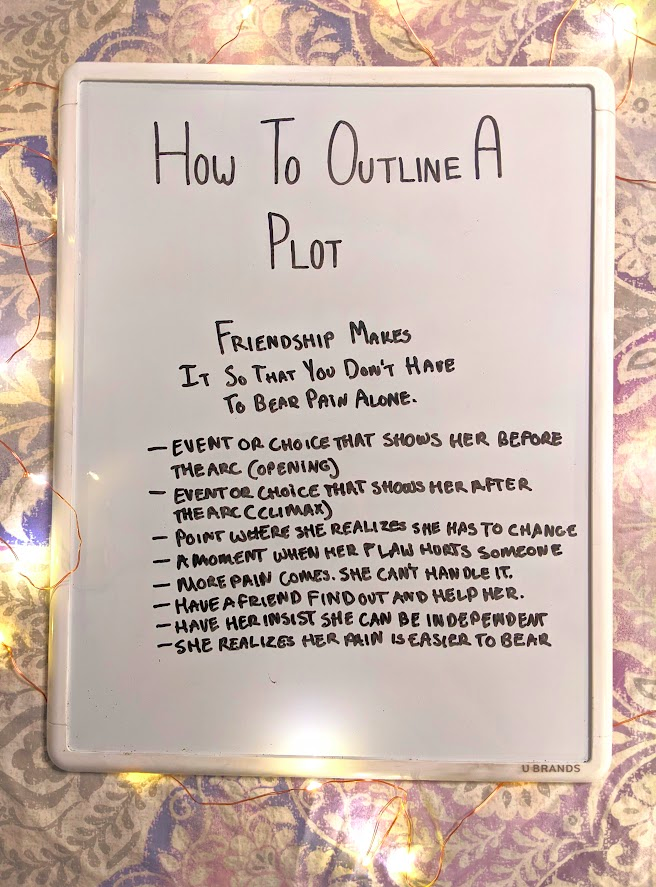

So let’s look at our theme first. In the last workshop, I listed a whole bunch of possible themes for the character we came up with in January. So I picked one for the Workshop that we can begin to work our plot around.

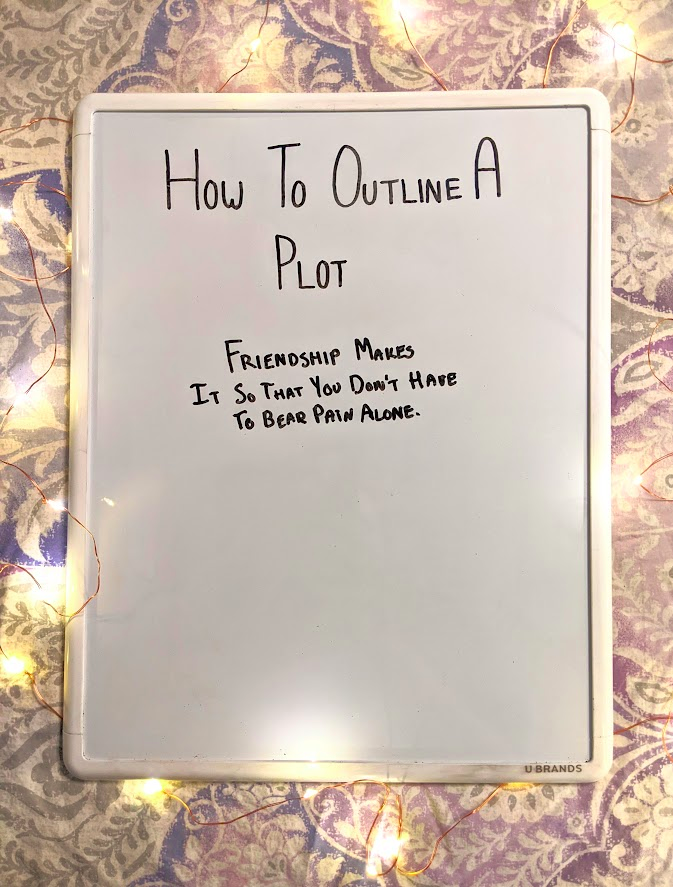

Plot and Character Arc

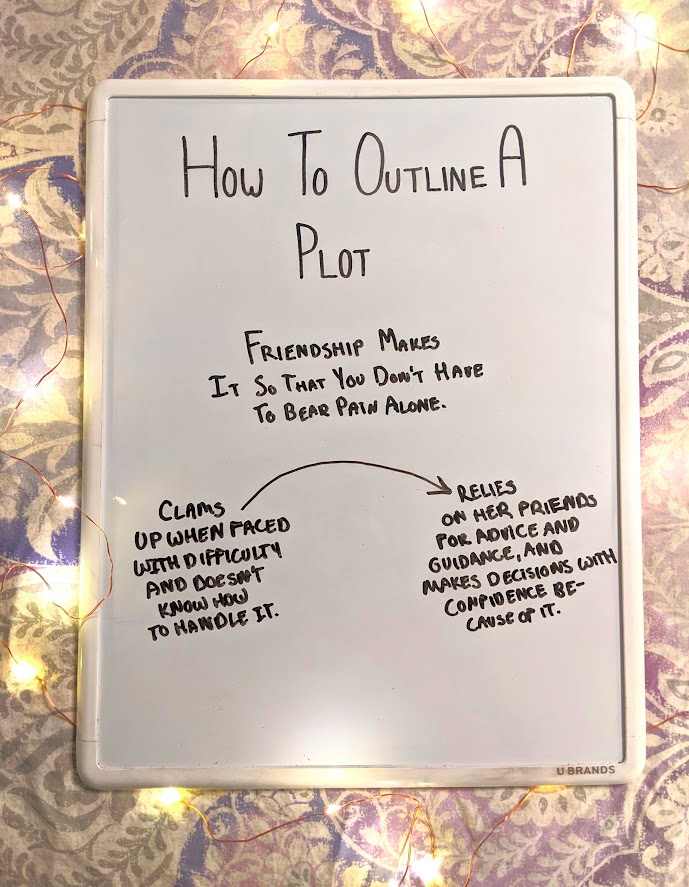

It is also important to make sure that the theme and plot will push the character arc forward. So let’s do a brief summary of the character arc by looking at how our character starts and how she ends up, considering the theme and her flaw.

What changes between these two descriptions forms the character arc, which will be the outline for our plot.

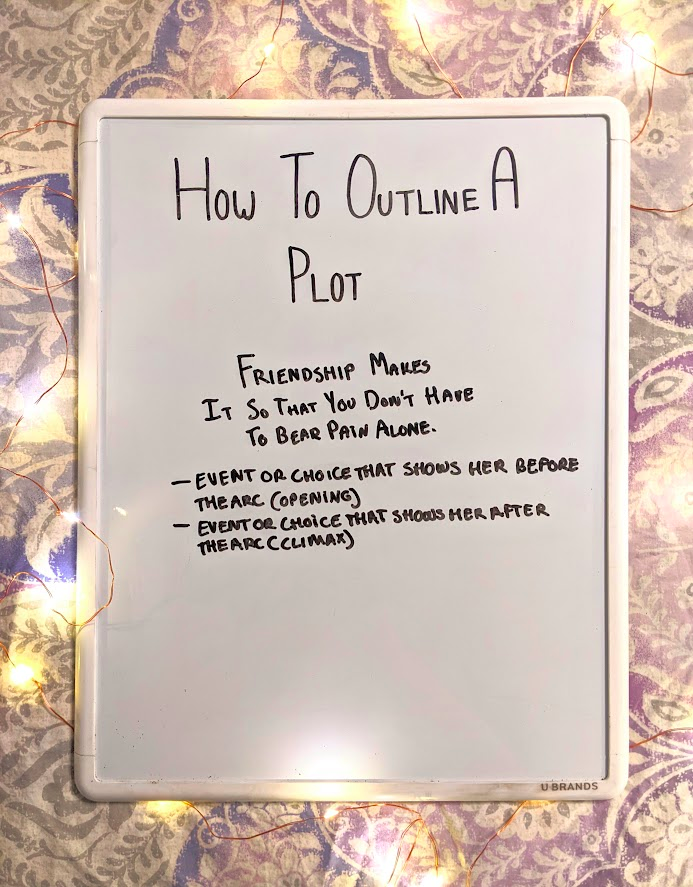

Coming Up with Plot Points

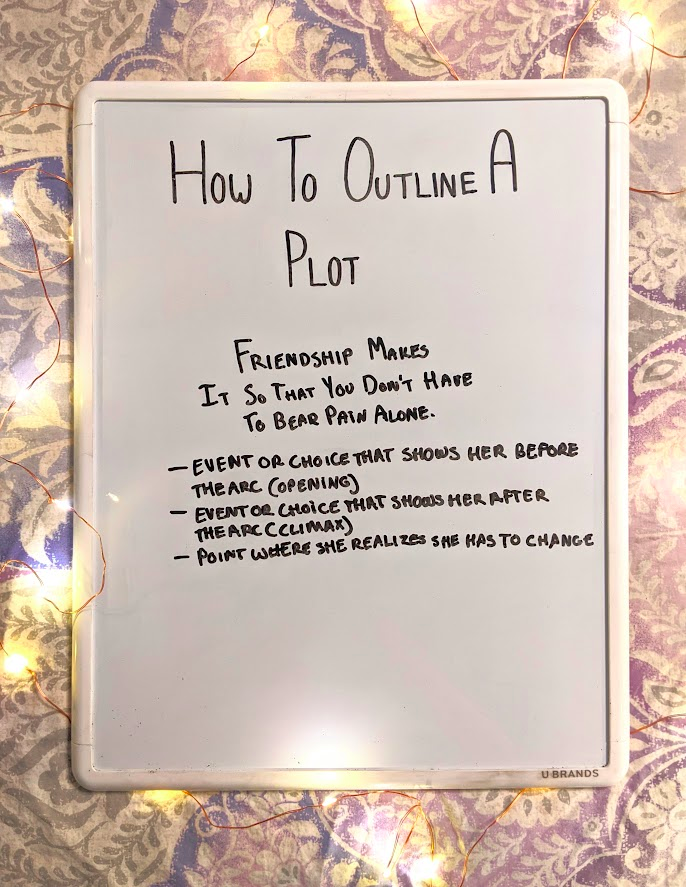

The next step is to come up with a list of possible plot events based on the theme and character arc developed above. If you have some ideas for scenes or concepts you’d like to explore, you can brain dump here.

For example, if you think your protagonist and her best friend might fight (hinting at the theme), or you’ve imagined your character will probably take a train somewhere, write those down here. You can flesh them out or expand on them as other events begin to fall into place.

If you don’t have any ideas to start out yet, this step can be a little daunting. But if you have any idea of how your character changes at all, you’ll already have two plot points — one that shows how the character begins the story, and one that shows them at the end.

These descriptions are loose on purpose. The events written down above could be a choice, a chapter following her everyday life, or an unexpected action scene (depending on the genre and the author’s preference.) Part of this is what makes this method great for pansters — you know the purpose of each scene without needing to come up with what happens in it right now, leaving that for when you sit down to write.

We can flesh these out more fully later, but for now we have a good idea of what to do in two scenes. Now, how do we move forward with this? Try to think of ways that this character could move forward in her arc.

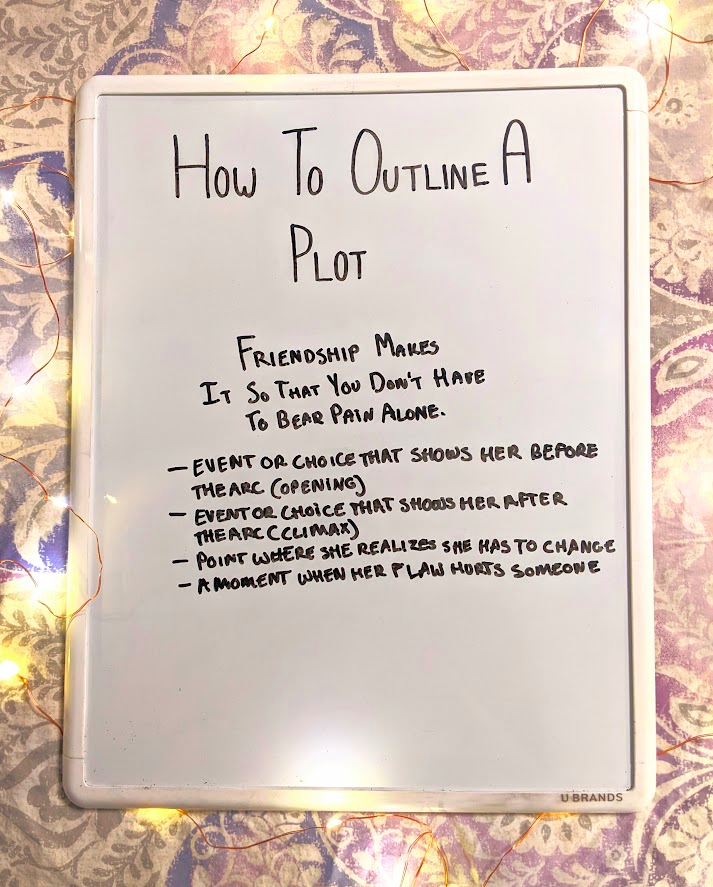

What could make her realize she has to change?

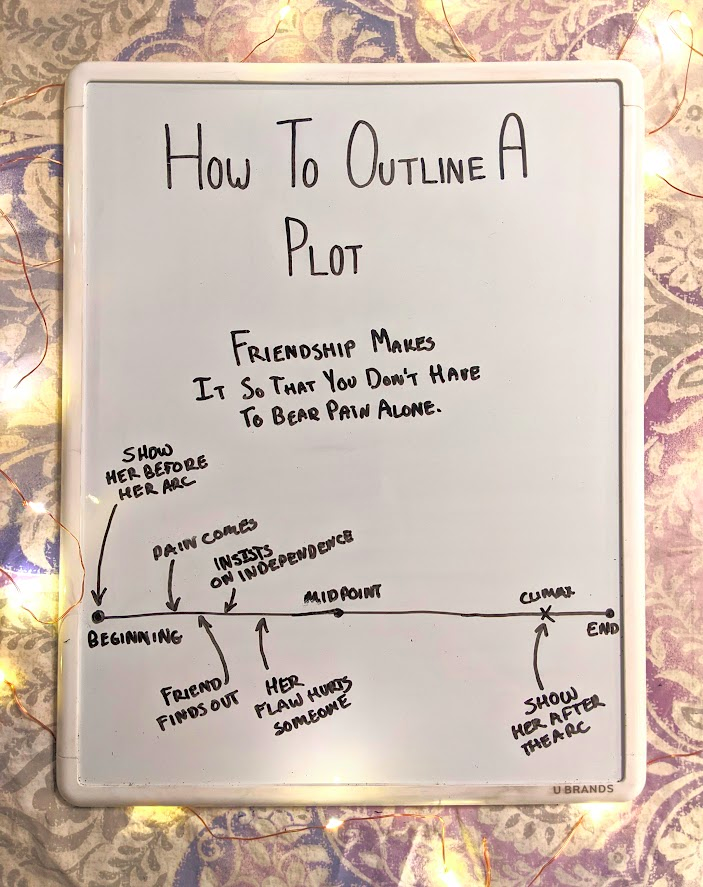

Having her flaw hurt someone could help her realize how damaging it is, thus encouraging her to change.

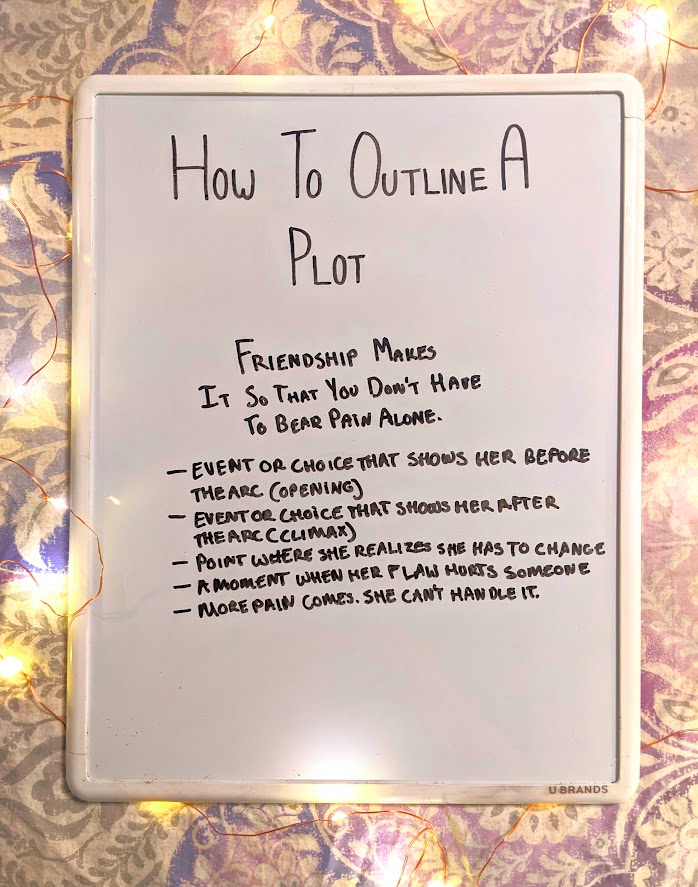

Now we just have to get her flaw to come up more often, and we can do that by pulling her out of her comfort zone, which would make it more difficult for her to control it. Since she fears pain and wants comfort, we can come up with a plot point that causes her pain or takes away her comfort.

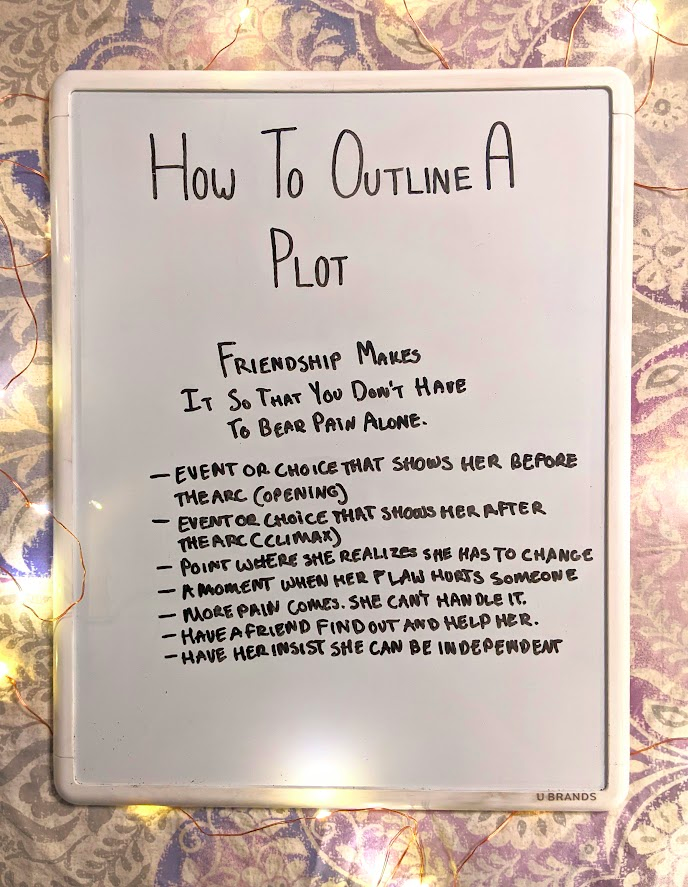

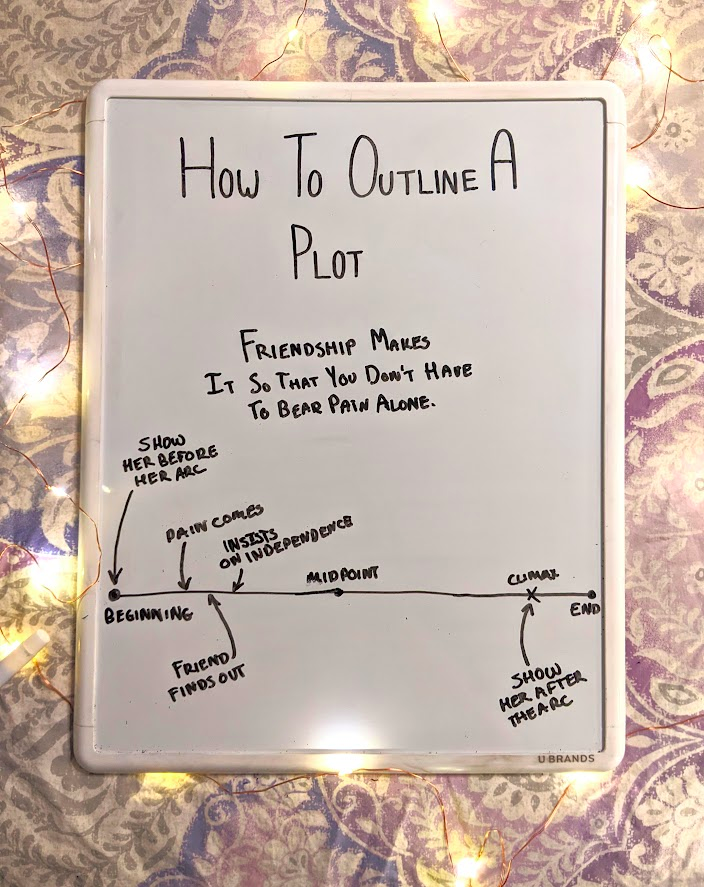

Now the main theme is supposed to be about friendship helping you through pain, so probably we should add a point where a friend notices she’s in pain and tries to help her, starting the questions in our protagonist’s mind about the best way to deal with pain, and if friendship is actually helpful in bearing it.

Having her insist that she is independent can show some of her flaw and demonstrate the antithesis to the theme. Plus, it adds another plot point.

But now we have to have her realize that she’s made the wrong choice after she refuses help or tries to avoid depending on her friends. I think the best way to do this would be to have her notice that the pain is easier to bear now that someone else knows about it and is willing to help her. This would spark bigger questions. If she can be a better person with help, is help all that wrong? Is her ego the only thing getting in the way of her dealing with pain well?

At this point, we’ve got a good amount of plot points. Of course, if you come up with more, feel free to write them down. The number of plot points will depend on how complicated you want your plot to be, whether you lean more toward pantsing or plotting, and how much you plan to stretch these events out.

I think I could make just the eight points above into a full-length contemporary novel. But it doesn’t have to be. Some of the events could be condensed into a single scene, and you could use these events to make a short story. For example, at the same moment that our protagonist learns of something or someone she’s lost, her friend could be in the same room and learns about it, too. The friend could then try to give help while the protagonist insists on being independent, thus starting an argument and hurting her friend with her flaw.

On the other hand, each of these events could be stretched out. Our protagonist could spend half the book hiding what she’s lost from her friends before one discovers it in a huge reveal near the end of the story. There would have to be a lot of other things in between these points, of course, but that comes with the genre, time period, and purpose of the story — things we can’t cover all in one workshop.

So for now, let’s try to order the ideas above into a cohesive plot.

Ordering the Plot Points

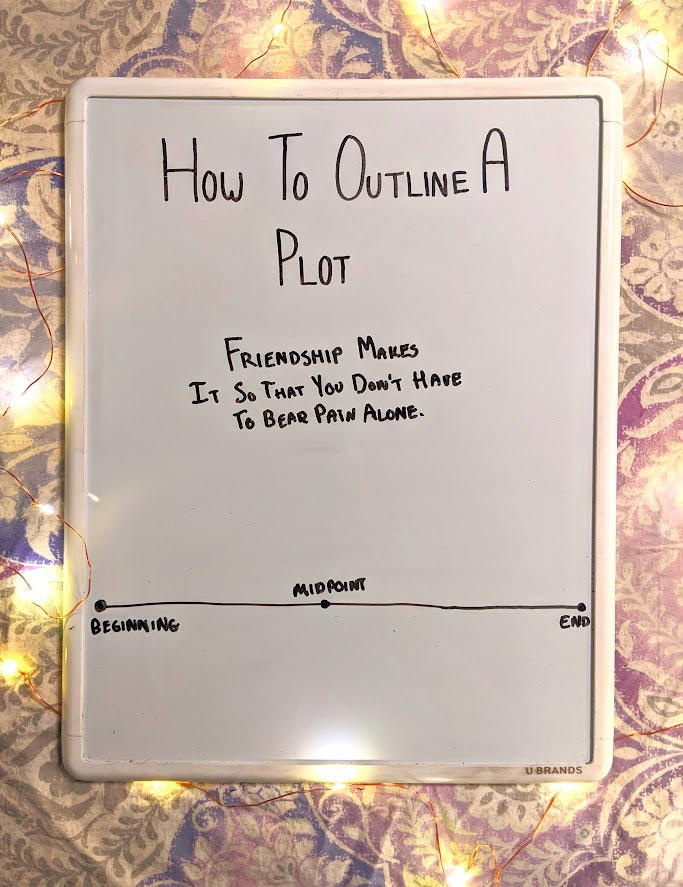

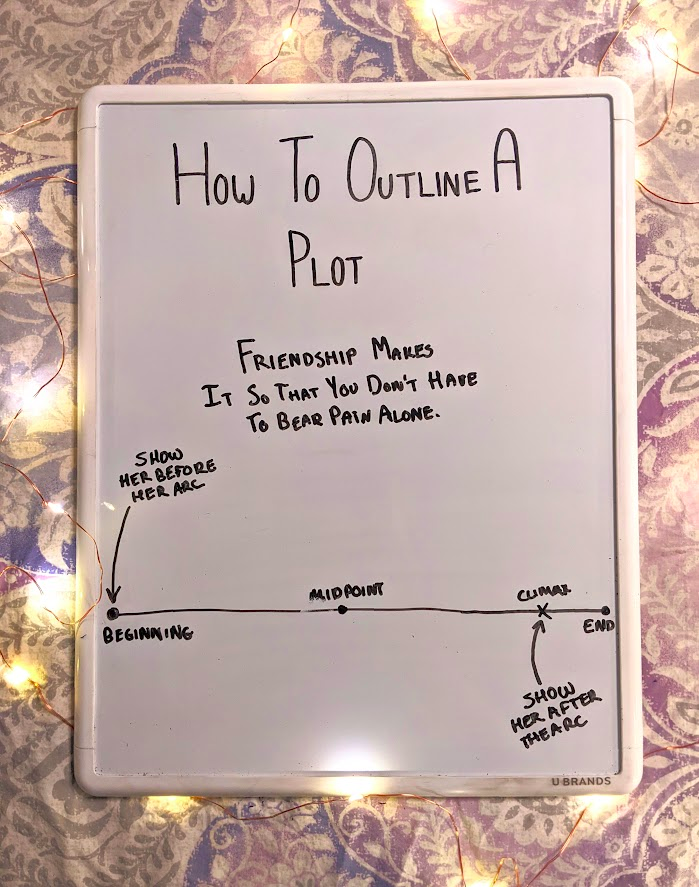

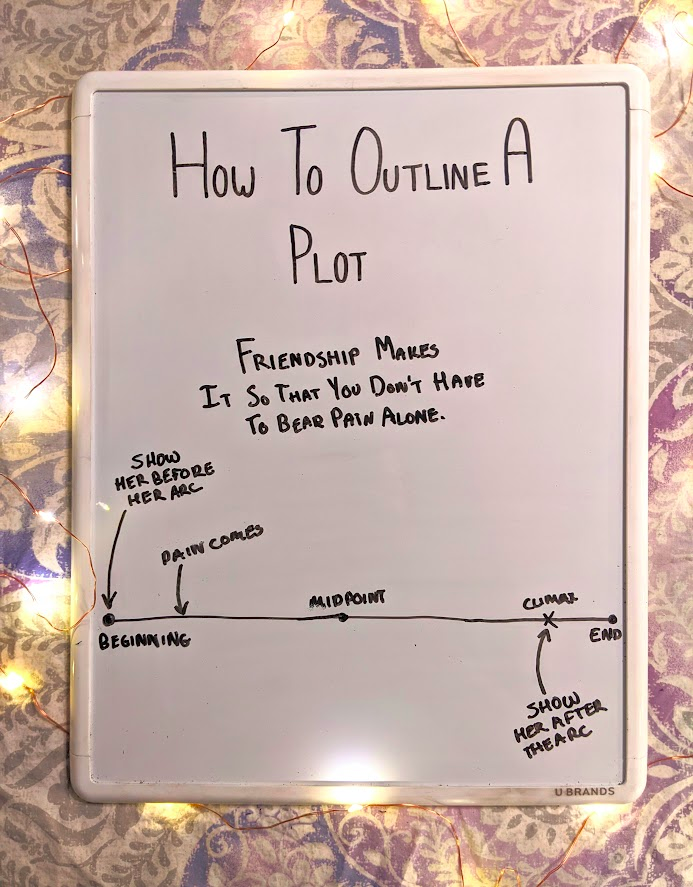

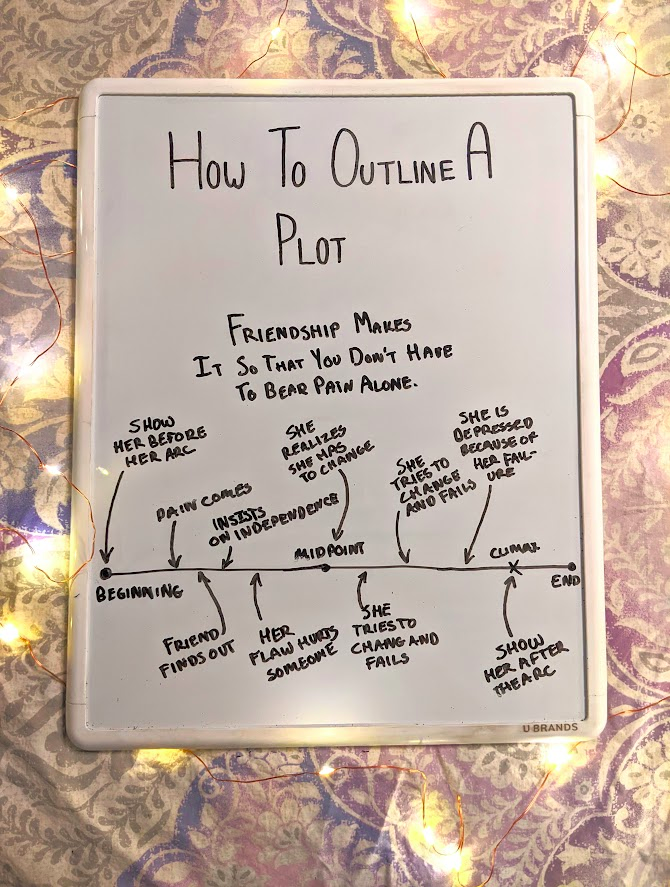

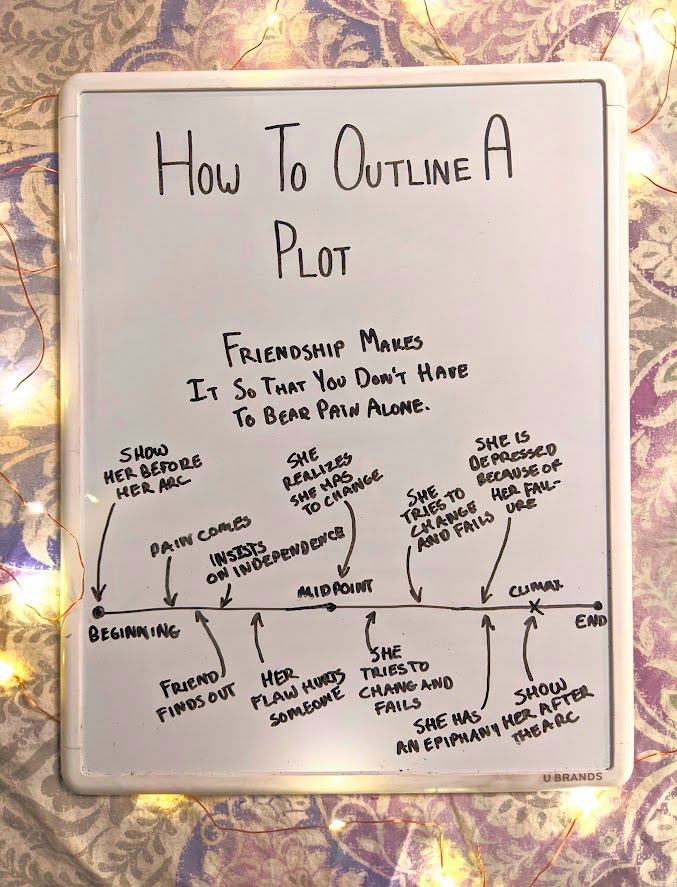

There are a few different ways to order plot points, from note cards to fillable plot templates. For now I’m going to use a basic plotline with plots organized along it.

Here’s are plotline, where the entire story will take place between the two dots on either end. All stories have a beginning, middle, and end, so let’s mark those in, too.

We want to show the protagonist and contrast her before and after the arc, so we already know where to place the first two of the scenes listed above.

The first event that really changes anything that we have written so far is when the pain arrives, so I’ll write that down somewhere in the first quarter of the plotline — exactly how far it is from the beginning depends on what other events, subplots, and character moments come between them.

The next few plot points are sequential, so we can fill those in right away.

As I mentioned before, you could save the friend finding out about her pain until the very end, or write it as the mid-book plot twist. Alternatively, it could happen in the exact same scene as the character experiences the pain. So the way I’m ordering these things isn’t the only way it can happen. There’s definitely a lot of freedom and flexibility with this method, so don’t be afraid to experiment with rearranging the plot events or switching them out.

Now our character is under a lot of stress, between whatever pain she’s enduring and the fact that her friend accidentally found out and now that she continues to insist she can bear it alone, even though she clearly can’t or shouldn’t. She seems to be under a lot of stress, which would make this a great moment for something else bad to happen, pushing her over the edge and making her flaw hurt someone she cares about.

Obviously, this bad thing could be something she’s been building towards and hoping won’t happen since the beginning of the book, or it could be a shocking twist that completely blindsides her and leaves her reeling from the shock, lashing out at others as she tries to regain her bearings.

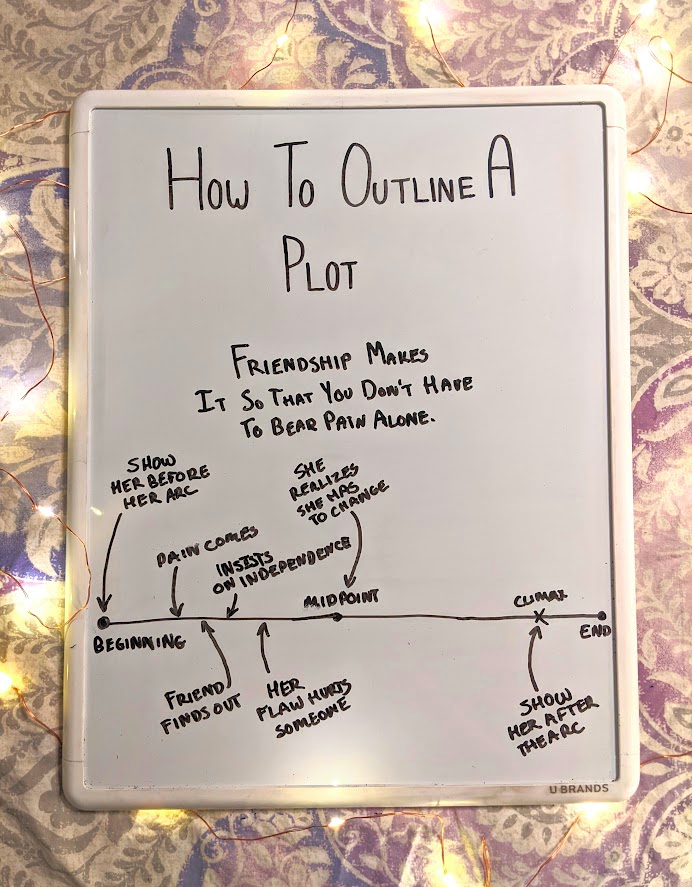

Now that she’s hurt someone with her flaw, she’ll probably realize she needs to change. She clearly cares about her friends (the entire theme of this book is about friendship) and so that can be the midpoint plot twist — she finally realizes that the flaw she’s either excused or seen as a virtue hurts others and is causing the stress she’s been under this whole time.

So she’s realized that she has to change. But we’re only toward the midpoint and change can’t really be that easy, can it? So let’s have our protagonist work for it a little bit.

I would have the temptation for her flaw — in this case either cowardice or self-centered thinking — to come up two or three times. I would let her fight against it, then ultimately give in. The temptations should come differently. They shouldn’t be the same thing twice. Maybe one is something she knows she’s struggled with, while the other is something brand-new she’s never experienced that brings the flaw out of her in a way she didn’t expect.

I imagine after trying so hard for the last half of the book and failing our protagonist would be pretty depressed. This, coupled with whatever pain she experienced in the beginning, is starting to weigh on her in a way that she can’t escape — bringing on her Dark Moment and causing her to despair.

We’re almost to the climax and her triumphant conclusion, but first we need the epiphany — the moment when the theme comes to light and our protagonist realizes she needs her friends to help her make it through conquering her flaw and facing the pain that has been chasing her since the beginning.

And now, at last, our protagonist can face the climax as a changed character. Her flaw is gone and in its place is the theme of the book, pushing her through this final test of her character and toward the conclusion.

There you have it! A loosely-outlined plot for the theme and character we’ve come up with throughout the year. Although this is far from the only way to outline, it is one easy way to come up with an idea of how you want your protagonist’s arc to flow into your theme and how your plot can help push both concepts forward. Hopefully it gives you some ideas for jump-starting your plot and coming up with the events that can change your protagonist’s perspective and highlight a truth that you want the whole world to hear.