Writers of all types — whether fiction or nonfiction, poets or journalists — have struggled with the seemingly insurmountable challenges that come with writer’s block. Sometimes, we have no idea how to proceed with our story. Other times, we are discouraged because we spotted an unexpected plot hole. Perhaps most frustratingly, there are times when we know exactly what to write next, but something feels off and putting the next few words on the page seems impossible.

Writer’s block has all different causes, from failing to understand your writing type to writing a scene with the wrong weather. Because it has so many different causes, it is impossible to provide a remedy for all of them in just one blog post. So this month, we’re dedicating a Workshop to a specific kind of writer’s block that seems to make the least sense and in some ways is the most difficult to overcome because of it.

I think all of us have stared at a page, known exactly what scene is supposed to take place, and have had no idea how to write it. Even as a dedicated plotter myself, with scene cards for every interaction that takes place in my books and a list of highly specific objectives for each and every scene, there are times when the words just aren’t coming. I hit an invisible wall and can’t move forward because I don’t know why I can’t write the next scene.

So today we’re going to look at three methods I’ve found helpful when faced with this particular type of writer’s block and several tips for how to use them in your own work.

Setting the Scene

In this workshop, we’re going to be exploring writer’s block through the story Sophia and I have developed in the Workshops throughout this year. Namely, we’re going to think through creative ways to write a scene where our protagonist, Hallie, is meeting up with one of her close friends for lunch. In this scenario, we know the scene matters because we have determined it’s the best way to introduce Hallie’s friendship and side character who’s going to be important to the plot later. We know they have to meet, they’ll reveal part of Hallie’s backstory through dialogue, and then leave. But writing it down just seems impossible.

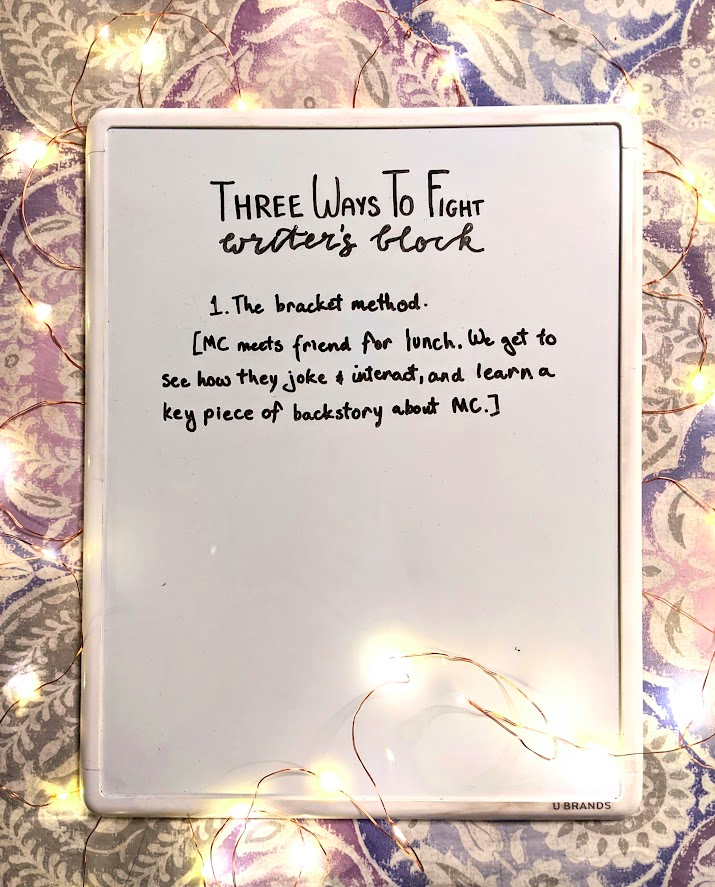

Method #1: The Bracket Method

The first method is by far the simplest of the three. There are times when you’ve hit writer’s block, can’t get past it, and just have to acknowledge that a particular scene is going to need a lot of editing, whether you write it now or later. The bracket method doesn’t focus on pouring a whole lot of energy into a scene that’s going to be cut up and edited later. In fact, it puts in almost as little energy as possible.

The bracket method simply describes the scene in very simple terms within brackets, to be fleshed out during the editing phase.

The brackets can have just a few words, or a whole paragraph. You can explain the specific purposes of a scene, or just leave it as basic as possible. In this case, we outlined the events that happen in the scene, and then give two reasons the scene has to happen. It’s very basic, but descriptions like this one can be much shorter or far longer. The point is to put as little effort as possible into outlining a scene, and then jump into the next one so that the project isn’t completely stopped by one scene. It’s used as a last resort when the scene your working on has become so draining that it is making you want to quit the entire project. The idea with the bracket method is to recognize such a scene as a temporary hurtle to be quickly overcome. Then, in the editing phase, you can come back and flesh it out, or perhaps you’ll realize the reasons you have listed could be better executed in another way. Alternately, if you can’t list a reason for the scene taking place, it’s possible it should be combined with another scene.

The bracket method is a super quick, very basic way to make sure you aren’t derailed by just one scene.

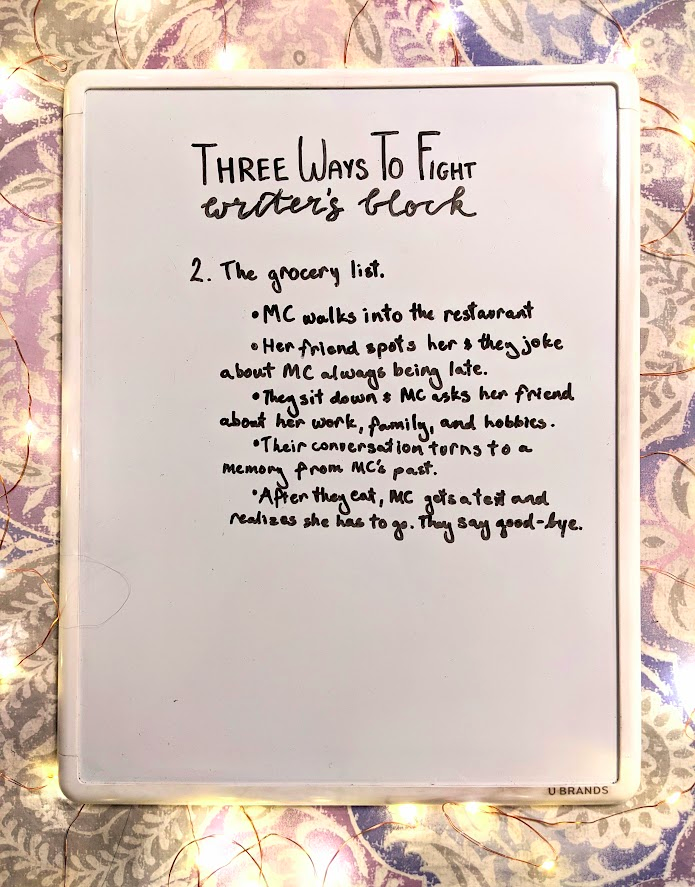

Method #2: The Grocery List

The grocery list is, essentially, an extension of the bracket method. With this method, you actually get a full scene out, so that even if it’s poorly written or in dire need of editing, at least it’s on paper.

Basically, the grocery list is like the bracket method, but extended to a series of bullet points that can each be fleshed out into a few paragraphs until eventually they make an entire scene. This can help when you know exactly what’s going to happen in specific detail, because having the sequence of events on paper is sometimes all it takes to break through writer’s block and write a full scene.

Here I have a grocery list of things I want to have happen in this scene. From there, you would take each point and make it longer, similar to the way formal nonfiction and essays are written. This method is brutally methodical, but it has helped me several times to just get through a scene — even if the emotions aren’t how I want them, the mood isn’t right, or there are times when it just seems boring.

Method #3: Add Conflict

This method is maybe my favorite because it seems so simple, yet is mentioned so little and has helped me through so many difficult scenes.

When nothing else seems to work, just add conflict.

This conflict can be as drastic as two friends starting out as enemies in a duel or as simple as one being afraid to tell the other the truth. Whatever it is should pose a question: Are these two friends actually enemies? Why is one hiding the truth from the other?

If your scene is something that happens regularly for the protagonist and is part of their routine (as in this particular example) it can be helpful to ask yourself what makes this day different.

In this case, what can we do to introduce conflict — whether internal or external, between the main character and her friend, or within one of them.

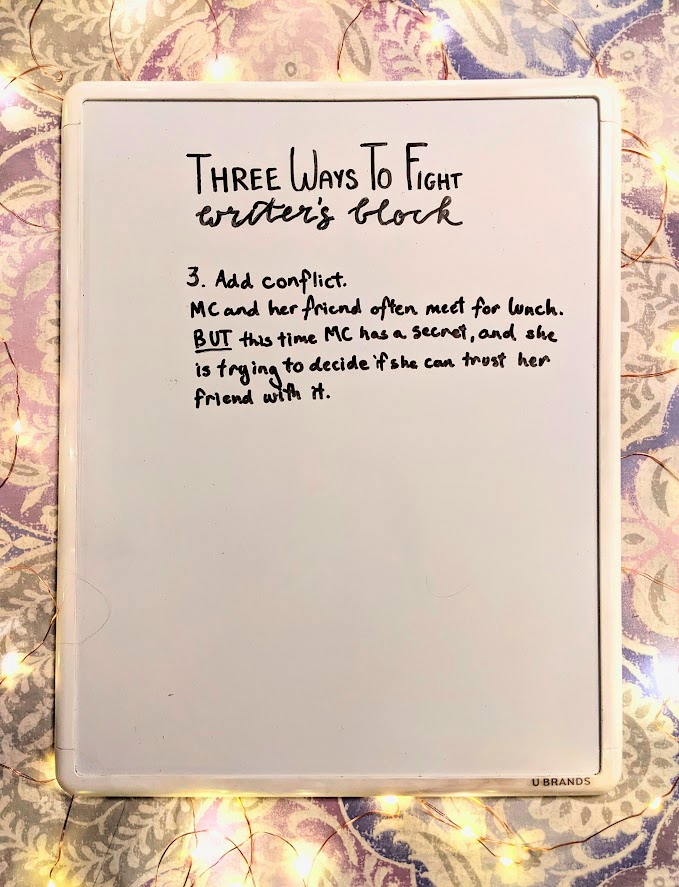

What if Hallie has a secret, and while she’s trying to have a normal lunch meeting with her friend, she’s also trying to decide whether or not to tell her.

To test if this works, we can look at if it brings up any questions in the mind of our readers.

In this case, it definitely does. Will Hallie tell her friend the secret? If she does, will she regret it? What is the secret? Who else knows about it? Why does Hallie want to tell this friend in particular?

It is these sorts of questions that will drive your scene forward and give it energy under the surface, making each interaction and event more meaningful and interesting both to you as a writer and your future readers. Whether internal or external, personal or interpersonal, conflict is a quick and easy way to drive your particular scene forward.

But it’s not the only way. It’s worth remembering that although there are dozens of ways to fight writer’s block, we only had time for three in this post, making it far from comprehensive. Find out what works for you, even if none of the method above do. Most of all, don’t let a lack of motivation end your project. Your story is worth seeing to the end.