There’s a lot of discussion in the world of storytelling about how to address politics in writing. From reboots that speak to social issues to brand-new stories with blunt political messaging, politicization has been a recurring issue especially in the last few years, and it doesn’t seem to be going away anytime soon.

But the writing community seems fairly divided on how to deal with it. One approach is just to ignore politics altogether — to intentionally remove any sort of political or social discussion from a novel because it could be seen as “preachy.” Others relish the inclusion of politics, and argue that it should be more prevalent: both sides should include political messaging in their stories, and it should become the focal point of most of our media.

These issues are important, after all. They can literally mean life or death for entire communities. Why not elevate a certain message, especially if we’re using that message to protect the vulnerable and possibly save lives?

To answer that question, I think it’s best to look toward one of the most successful — and political — American novels of all time, Uncle Tom’s Cabin.

Uncle Tom’s Cabin

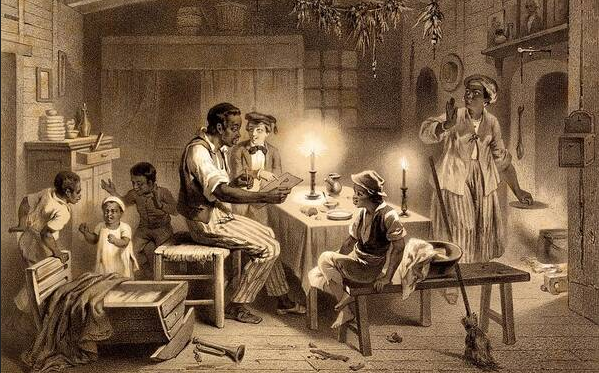

Set in the pre-Civil War South, where slavery was not only practiced but also considered a normal part of life, Uncle Tom’s Cabin wastes no time in addressing the issue head-on. Its titular character, Uncle Tom, is a wise old slave respected in his community and even by his master. But when his owner faces difficult financial decisions, he doesn’t hesitate to sell Tom to a different area of the country.

Separated from his wife and the family he’s formed within his community, he faces an uphill struggle to maintain his humanity in unspeakably inhumane circumstances. He strives to hold to his values while those around him abandon them or at the very least question them, and finds himself facing incredible suffering because of it.

Throughout his journey, he meets people of all kinds and creeds, from fierce abolitionists to cruel slave owners and everything in between. Through his eyes, we get a window into dozens of different philosophies on slavery by the author taking us into multiple different perspectives, often for just a few chapters. And that aspect to her work is the biggest part of why it worked.

The Power of Nuance

Uncle Tom’s Cabin spares no words in exploring every facet of slavery — from the perspective of slaves and slave owners, abolitionists and orphans. It reveals both the cruelty and the complexity of the issue as it existed in the pre-Civil War South. And yet it became the best-selling American novel of the 19th century, in a time when slavery was still a prevalent force and a hot-button political issue.

But these two seemingly contradictory truths are actually how political works can succeed, even in the contemporary climate, which is no more emotionally charged than our nation was at the edge of America’s bloodiest war.

That’s because political content in today’s media often involves a random line, a single impassioned monologue, or a sermon delivered from one character to another — and the audience. The reason these comments seem so out of place and preachy is because they are. The ideas don’t serve to support the rest of the story. They don’t enhance the theme of the entire book. And they definitely don’t develop any of the characters, at least not in an organic or believable way.

So if you aren’t writing an inherently political work, skip the political messaging. Focus on a different set of ideas, a new struggle, or a political force disconnected from the contemporary conversation.

But writing an inherently political novel is not impossible. In fact, it is even conceivable for these kinds of works to succeed in the market. Uncle Tom’s Cabin certainly did. Yours can, too.

You just have to make sure your theme — the underlying message of your entire work — is, in its purest form, political.

The theme of Uncle Tom’s Cabin — the question it wants the reader to walk away with — is: What is the value of freedom, and is it ever worth surrendering for the sake of comfort?

That question is undeniably political. In Harriet Beecher Stowe’s day, asking that kind of question would almost immediately include the discussion around slavery. In other words, the debate around slavery was the contemporary manifestation of that particular question in Mrs. Stowe’s day.

There are two things to note here.

The first is that even though Uncle Tom’s Cabin addresses a political issue (slavery) it does so by asking a deeper question about freedom and comfort. If you want to write about abortion, for example, ask yourself what deeper ideas and questions are really at play here. What underlying question is the culture asking when they fight over pronouns, immigration, or gun control?

These issues are not irrelevant political talking points, here today and resolved in a few years. They are contemporary reiterations of the questions human beings have asked and waged war over since the dawn of time. Understanding those questions and incorporating them into your work will give your novel a timelessness that it can’t achieve by only discussing a contemporary issue.

The second is that your book should only discuss that issue. If your political ideas come up just once or twice, or the issues you’re addressing are only seriously examined in one scene, then you aren’t writing an inherently political work, and the political ideas should be done away with for the sake of the other elements of your storytelling. Your theme is likely compelling, your characters may be colorful, and your worldbuilding could be ingenious, but your readers are going to miss all of that for the political messaging that feels out of place and preachy. Let those other elements shine by cutting the commentary.

But if the core of your novel is addressing a political issue, then by all means address it and do it well. The best way to do this is to look at that one issue from all sorts of perspectives. Mrs. Stowe could have just as easily told the entire story just from Uncle Tom’s perspective. Most of her ideas and arguments would have been maintained. But it would have lacked the depth it carries. It would have seemed one-dimensional and flat — justified, for sure, but feeling more like a political speech than a story.

Instead, she looked at the issue of slavery from all angles. She dove into the mindset and perspective of every individual who could be involved in the issue, from the calloused and disinterested slave buyer at an auction to the abolitionist who realizes the only way she can truly protect an abused orphan is by buying her — thus participating in the very system she swore to destroy. She understood the philosophy of slaves who would trade freedom for comfort in an instant while also showing us the world through the eyes of those who risked everything, even enduring extreme suffering and pain, to achieve liberty.

If you want to write about a political issue in a way that’s compelling and believable, you must both understand and demonstrate the nuance that comes with every issue. And the way to do that is understanding the arguments and philosophies of all sides (because there’s always more than just two) and then showing those arguments clearly to the audience.

Without that, they will feel preached at, understanding your logic but failing to see it endure counterarguments. But with those new perspectives, your philosophy becomes compelling to even the disinterested, the uneducated, and the unconvinced while also coloring your world by filling it with characters from diverse and unique perspectives.

Abraham Lincoln is reported to have told Ms. Stowe that her book started the Civil War. Our pens have the ability not only to bring truth and light to painful and contentious situations, but also start wars, bring peace, and end injustices. Authors play an integral role on the world stage, even if that role is often unseen or unacknowledged by history textbooks. Ignoring that power is not only naive, it also shirks the unique duty that authors have to bring truth to areas of suffering. But that power must be wielded well. And if we can learn from the authors who came before us, following in their legacy and imitating their wisdom, we’ll be able to use that power to end the injustice we see in our world today.

Let us know:

Can you think of any stories addressing contemporary controversy that you’ve enjoyed? Did they use the techniques we highlighted here?

Hi! My name is Mara, and I’m a Christian artist, violinist, and blogger. I remember the day that I decided that I would learn something new about what makes a good story from every book I picked up — whether it was good, bad, or a mixture of both. I use this blog as a way of sharing some of the tips and tricks I’ve learned, and highlight which books, cartoons, and movies have taught me the most about writing an awesome story.

I’ve always thought the difference between political art, and the preachy political activism in fiction, is simple. Political art makes you think, but political activism tells you what to think.

I think yes and no. I’ve heard that idea applied to education and philosophy, which I agree with. However, political literature is different because it’s not merely meant to inform, but also offer a clear agenda (or what we call a theme in nonpolitical works.) Uncle Tom’s Cabin was pretty clear with what it wants you to think: slavery is wrong. I don’t think that’s a bad thing. The difference between political art and political activism is that one is consistent, nuanced, and stands up against arguments, and the other reads like a simplistic fable that can’t stand against arguments and offers a black-and-white view of reality.